Why Jamaican Athletes Running for Turkey Just Won’t Be the Same

A growing trend of Jamaican athletes switching allegiance to countries like Turkey has raised eyebrows — and for good reason. It may look like an opportunity for greater financial support or international exposure, but the truth is, running for another country is not the same. Especially when that country isn’t Jamaica.

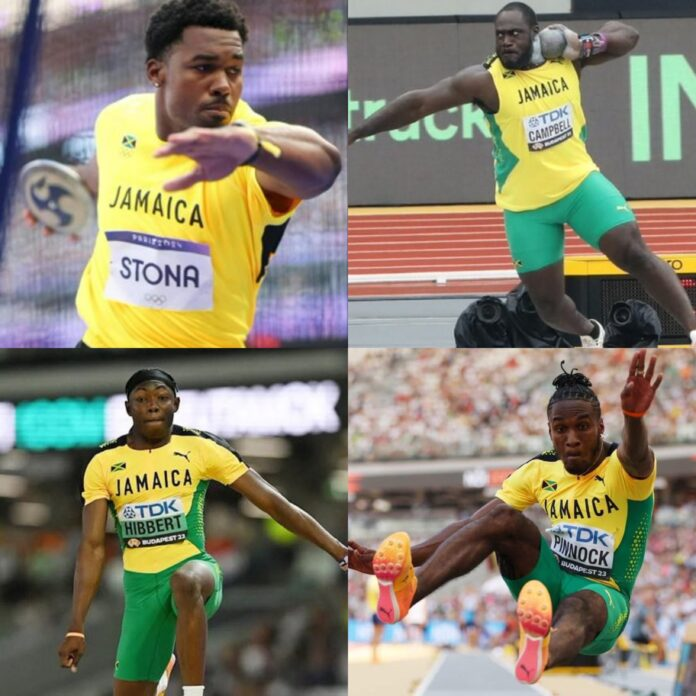

A significant shift is underway in Jamaican athletics as top athletes—Wayne Pinnock, Jaydon Hibbert, Rajindra Campbell, and Roje Stona—reportedly switch national allegiance.

- Wayne Pinnock, Olympic silver medalist in long jump and NCAA champion, is finalizing his transfer.

- Jaydon Hibbert, triple jump phenom and NCAA star, is expected to complete his switch within 20 days after placing fourth at the Olympics.

- Rajindra Campbell (shot put bronze) and Roje Stona (discus gold, Olympic record) have already completed their transfers, marking historic firsts for Jamaica in Olympic throwing events.

This trend reflects a growing movement of elite Jamaican athletes seeking better financial and structural support abroad.

Reports now indicate that Jamaican Olympic medalists Rajindra Campbell and Roje Stona are switching allegiance to Turkey, lured by substantial financial incentives.

- The reported package includes a $500,000 USD signing bonus, monthly financial support, and performance-based bonuses for medals at major events.

- Sources such as ESPN and Sportsmax confirm the athletes’ decisions were influenced by the promise of greater financial security and career support.

Campbell and Stona made history for Jamaica at the 2024 Paris Olympics in the shot put and discus events, respectively. Their transfer marks a major loss for Jamaica’s field athletics program.

Jamaica’s sprint culture is unmatched.

We don’t just produce fast athletes — we live and breathe track and field. From Champs to the streets of Kingston, running is part of the national DNA. Our coaches, climate, competition culture, and community pressure create an unmatched training environment. You can’t replicate that with money alone.

Language and culture matter.

Representing a country where you don’t speak the language or understand the social rhythms makes everything harder — mentally, emotionally, and even athletically. You’re no longer running for your people, your school, your parish — you’re running for a passport and a paycheck. That changes motivation. That changes pride.

Brand Jamaica has bragging rights.

When a Jamaican steps on the track, the world pays attention. We’ve earned that respect through decades of dominance. When you switch to a country like Turkey, you lose that instant recognition, that aura. You’re not “the Jamaican sprinter” anymore — you’re just another import.

And let’s talk economics.

Turkey is a nation of over 85 million people, with a GDP of $1.1 trillion. Jamaica? Just 2.84 million strong, with a GDP of $19.4 billion. If it really comes down to resources, why can’t Turkey build their own sprint program? Why are they relying on Jamaican talent to carry their Olympic dreams?

Can Turkey even maintain Jamaican standards?

It’s one thing to recruit elite talent. It’s another to support and sustain the level of discipline, mental focus, and raw intensity that Jamaican sprinting requires. If they can’t develop it from the ground up, can they really nurture it in the long term?

At the end of the day, switching allegiances might offer short-term gain, but it comes at a cost — a loss of identity, heritage, and connection. No amount of money can replace what it means to run for the Black, Green, and Gold.

Running Away From Home: Why Jamaican Athletes Switching to Turkey Isn’t Just Business

While it may appear to be a simple business decision — better funding, more opportunities, and fewer bureaucratic hurdles — the move raises deeper questions about identity, pride, and the long-term cost of trading patriotism for a passport.

Let’s be clear: Jamaica is a sprinting superpower. We didn’t buy our way to the top — we earned it. From dusty tracks in rural parishes to the grand stage of the Olympic Games, our athletes rise through a system built not on billion-dollar budgets but on grit, community, and a deep cultural reverence for athletic excellence.

Switching flags for money might provide access to European facilities and sponsorships, but it comes with emotional and cultural dislocation. Running for a country where you don’t speak the language, don’t understand the culture, and don’t have deep-rooted connections is more than just an administrative change — it alters the very fire that fuels performance. It’s not the same when you’re not running for your people, your school, your country. That spirit can’t be outsourced.

Jamaican athletes carry more than just speed; they carry a global brand. The Black, Green, and Gold evokes respect on the track. The moment a Jamaican steps onto the starting line, there’s an expectation — not just from the crowd, but from history. Usain Bolt didn’t just win medals; he built a legacy tied intrinsically to the flag on his chest. When you run for Turkey, you don’t carry that weight. And with that, you lose a part of what makes a Jamaican athlete iconic.

This also begs the question: why is a wealthy country like Turkey, with a population of over 85 million and a GDP exceeding $1.1 trillion USD (2023), unable to develop its own sprinting programme? Jamaica, with a population of just 2.84 million and a GDP of $19.42 billion USD, has managed to create a sprinting dynasty. If Turkey can’t build its own athletes, how can it truly support and sustain the high standards Jamaican athletes require to thrive?

Furthermore, athletic greatness doesn’t come from resources alone. It comes from the grind, the local rivalries, the shouts from a coach who knows your mother, and the dreams rooted in a small island with a big heart. When Jamaican athletes trade in their roots for a foreign track, they’re not just changing jerseys — they’re leaving behind a community that helped shape their greatness.

The Jamaican government and athletic bodies must now take this trend seriously. If we don’t create a more supportive system for our athletes — one that rewards excellence without them having to look abroad — we risk a talent drain that could eventually erode our global dominance.

Yes, athletes have every right to chase opportunity and secure their futures. But we must ask: at what cost? When a Jamaican wins gold, it’s not just a personal triumph — it’s a national celebration. That kind of pride doesn’t come with a Turkish passport.

About the Author

Margaret Knight is a journalist/commentator with a passion for Jamaican culture and international athletics.