Stateless and Stranded: U.S. Soldier’s Son, Jermaine Thomas Deported to Jamaica

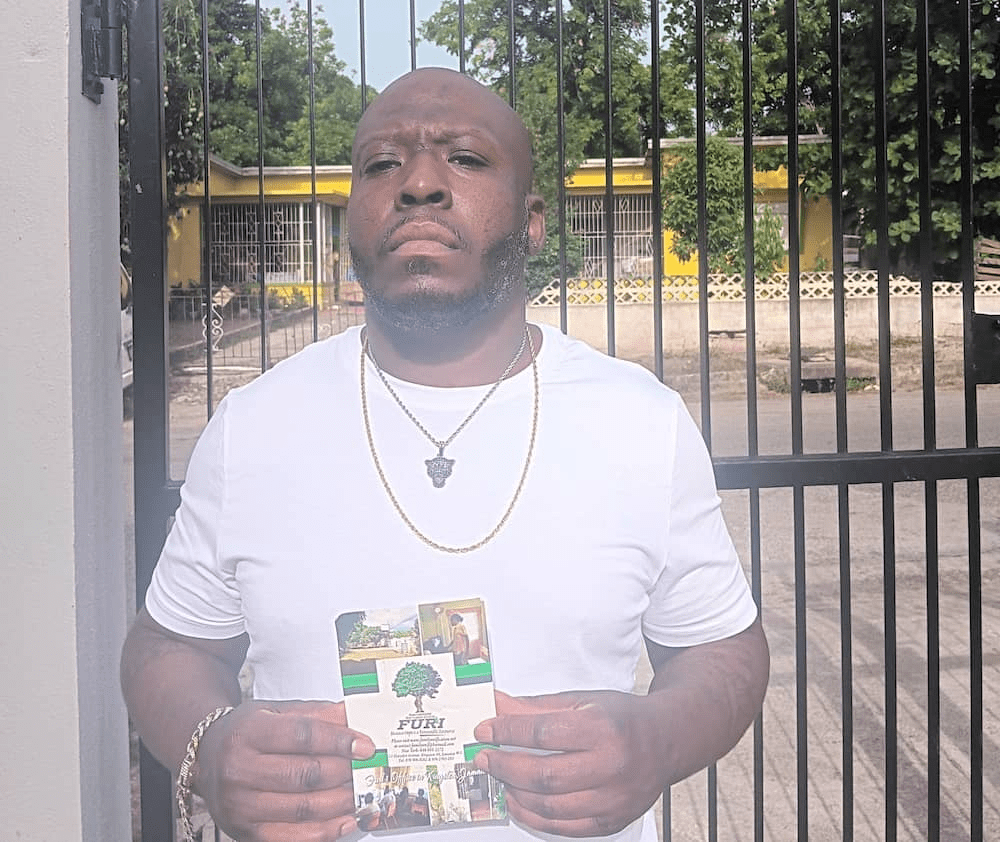

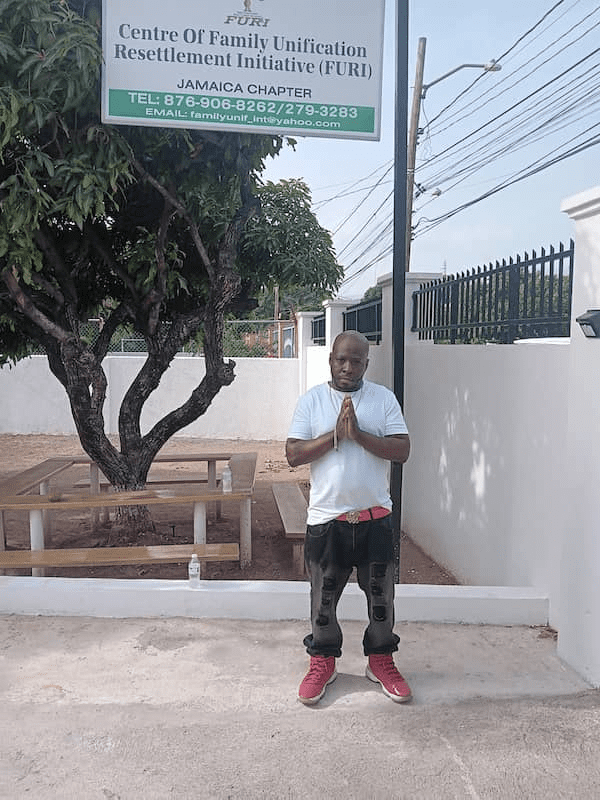

Ten years after his name appeared in a landmark case before the U.S. Supreme Court, Jermaine Thomas now finds himself exiled to a country he’s never known. Born to a U.S. Army father on an American military base in Germany, Thomas was deported last week to Jamaica — a place he’s never lived, has no citizenship in, and where he now wanders as a man without a nation.

Thomas, 38, says he was shackled at the wrists and ankles during his deportation flight from Texas to Kingston. As the plane soared above the Gulf, his thoughts turned dark. “I’m looking out the window on the plane,” Thomas told The Chronicle, “and I’m hoping the plane crashes and I die.”

Thomas is stateless. According to court documents, he holds no recognized nationality — not from Germany, where he was born in 1986; not from the United States, where his father served nearly two decades in the military; and not from Jamaica, where his father was born. With no citizenship and no homeland, Thomas was deported following a minor misdemeanor arrest in Texas, setting off a bureaucratic freefall that landed him on foreign soil.

From Army Bases to Homelessness

Normally, a child born to a U.S. citizen father deployed to a U.S. Army base in Germany is likely a U.S. citizen at birth. Generally, children born outside the U.S. to U.S. citizen parents are considered U.S. citizens at birth if the parent(s) meet certain physical presence or residence requirements in the U.S. before the child’s birth. Military service counts towards these requirements, so a deployed service member’s time on active duty is considered.

So why didn’t Jermaine Thomas receive citizenship, even though his father was a U.S. citizen and a long-serving Army soldier? Could this be racism and coupled with the fact he didn’t have the right legal representation to hear his case?

This situation often arises when a child is born to a U.S. citizen parent serving in the military or working overseas. The specific laws and their interpretation can be complex, and the case of Jermaine Thomas, born on a U.S. Army base in Germany, is an example.

Here’s a breakdown of the key elements:

- Physical Presence Requirement:U.S. immigration law has historically included a requirement for a U.S. citizen parent to have resided in the U.S. for a certain period before the birth of a child born outside the U.S. for that child to automatically become a U.S. citizen.

- Statute in Force:This refers to the specific immigration law, often 8 U.S.C. § 1401, that was in effect at the time of the child’s birth.

- Jermaine Thomas’s Case:In this instance, the “statute in force” meant that despite his father being a U.S. soldier and Jermaine being born on a U.S. military base in Germany, he wasn’t automatically a U.S. citizen because his father’s physical presence in the U.S. prior to his birth didn’t meet the requirements of the law at that time.

- Deportation:Because of this, Jermaine Thomas, after being raised in the U.S. since childhood, was ultimately deported to Jamaica, a country he had never lived in.

- Supreme Court:The case went to the Supreme Court, which upheld the lower court’s decision that his father did not meet the physical presence requirement.

While not the only factor, racism and systemic bias likely contributed to Jermaine’s situation in multiple ways:

- Disproportionate Scrutiny: Black and brown immigrants are often more aggressively policed, detained, and deported.

- Unequal Legal Assistance: Poor, minority communities — especially those born abroad — are less likely to get legal advocacy, which is essential in complex nationality cases.

- ICE and DHS Errors: Immigration enforcement has a long history of wrongfully detaining or deporting U.S. citizens, and these mistakes disproportionately affect Black and Latino individuals.

Combine that with the military’s own history of disenfranchising Black service members and their families, and it paints a picture of systemic neglect — if not outright racialized injustice.

Maggie Quinlan Journalist at the Austin Chronicle give a summary of the case.

✅ Bottom Line:

- Yes, Jermaine Thomas likely should have received U.S. citizenship at birth or through his father.

- The fact that he didn’t is likely due to a mix of legal inequality (especially before 2017), bureaucratic neglect, and systemic racism.

- His deportation, especially with no ties to Jamaica, is a failure of justice — both legal and moral.

Thomas says he barely remembers Germany. Raised in a military household that moved frequently, he has hazy early memories in Washington state and spent most of his life in Texas. After his parents divorced, Thomas was eventually sent to live with his biological father in Florida, a retired Army veteran. His father died in 2010 from kidney failure.

Thomas’ life unraveled from there — years of instability, poverty, and time in jail. Most recently, he was working as a janitor in Killeen, Texas, before being evicted. That’s when he says the chain of events began: police arrived at his residence responding to a report about his dog. They arrested him for misdemeanor trespassing, even though he says he had committed no crime. After 30 days in Bell County Jail, Thomas expected to be released. Instead, he was transferred into the custody of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

From there, things got murkier.

He was bounced between detention centers in Waco and Conroe, Texas, where he says ICE officials expressed confusion about his citizenship status. “You keep explaining to me that I’m being detained in suspended custody,” Thomas recalls being told, “but if I don’t have a release day and I don’t get to see a judge, that’s pretty much a life sentence.”

Frustrated, he filed a complaint with the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Inspector General, but says he received no response.

A “Walk of Shame” on Deportation Day

In late May, Thomas was loaded onto a deportation flight to Jamaica — a country he’d never visited and with which he had no legal ties.

Tanya Campbell, another deportee on the same flight who had recently completed a prison sentence in New York, said she first noticed Thomas surrounded by nearly a dozen ICE officers as he was led to the plane. “It was like a walk of shame,” she said. “They had him shackled like a fugitive.”

Thomas says he was seated in the final row — Row 31. After the plane landed, he sat motionless as others rushed to deboard. Then, an ICE officer reentered and reportedly told his colleagues: “I don’t have records for more than half of these people. There’s something wrong.”

Neither ICE nor DHS responded to repeated requests for comment.

A Stranger in a Strange Land

Now in Kingston, Thomas says he feels lost and deeply alone. He doesn’t understand Jamaican Patois, doesn’t know how to find work, and isn’t even sure whether he’s legally allowed to be in the country.

“I don’t know who’s paying for this hotel room,” he said. “I don’t know how long it’ll last. I don’t know what I’m supposed to do now.”

He believes the U.S. has betrayed both him and the memory of his father. “If you’re in the U.S. Army and the Army deploys you somewhere, and you’ve got to have your child over there, and then your child makes a mistake after you die — are you going to be okay with them just kicking your child out of the country?” he asks. “It was just Memorial Day. Y’all are disrespecting his service and his legacy.”

As Thomas faces a future full of uncertainty, one thing is clear: He is a man born into the service of a country that now refuses to claim him.

That’s a deeply important and troubling question — and it reflects a broader issue at the intersection of international law, immigration policy, and human rights.

Why the Andrew Holness government (or any receiving government) might allow someone like Jermaine Thomas — who says he has no Jamaican citizenship — to be deported to Jamaica:

1. Deportation Agreements & Bilateral Cooperation

Jamaica, like many countries, has bilateral agreements with the United States to accept deportees who are believed to be of Jamaican descent. If the U.S. government submits travel documents claiming someone was born to a Jamaican parent, the Jamaican government may accept them even without conclusive proof of citizenship.

- Jermaine Thomas’ father was born in Jamaica, and that may have been enough for ICE to argue that Jamaica should receive him — even if Thomas never claimed Jamaican citizenship or held a Jamaican passport.

2. Weak Documentation and Appeals Process

In many deportation cases, stateless individuals or people with unclear citizenship status get caught in bureaucratic gaps:

- They may be wrongly presumed to have citizenship in a country just because of parentage.

- Receiving countries (like Jamaica) sometimes don’t rigorously verify those claims, especially under U.S. pressure or to maintain diplomatic relationships.

3. Lack of a Stateless Person Protection Policy in Jamaica

Jamaica does not have a comprehensive legal framework for dealing with stateless persons. That means:

- There is no formal process for determining statelessness.

- There is no guaranteed protection against being arbitrarily received or refused entry.

As a result, a person can be dropped into Jamaica without any clarity on their legal status, as appears to have happened with Thomas.

4. The Role of Appearance and Assumptions

There is often an unspoken racialized element: deportees who are Black and whose family has Caribbean roots may be sent to places like Jamaica even when legal status is murky. As Thomas himself put it, “It may be he’s only there because of his ‘appearance.’”

So, Why Is the Holness Government Allowing This?

Political Pressure and Limited Leverage

Jamaica — a smaller country with close ties to the U.S. — may feel pressure to comply with U.S. deportation demands.

Refusing deportees can create diplomatic friction, especially if the U.S. has already issued what it considers a valid “deportation order.”

- Assuming Thomas is Jamaican based on limited or incomplete data from ICE.

- Not wanting to challenge U.S. deportation policy or disrupt diplomatic norms.

- Not having internal legal tools to push back on receiving potentially stateless individuals.

- Lack of political will to stand up for people who aren’t formal citizens, even if they have Jamaican roots.

Should They Be?

Arguably no — international human rights law urges states not to render people stateless, and certainly not to accept individuals without verifying citizenship.

Jamaica could:

Work with international bodies (like the UNHCR) to ensure that no one is unjustly left in limbo.

Demand proof of citizenship before accepting deportees.

Establish a statelessness determination procedure.