Ghanian President John Mahama Calls Out the Silent Weapon of Colonisation

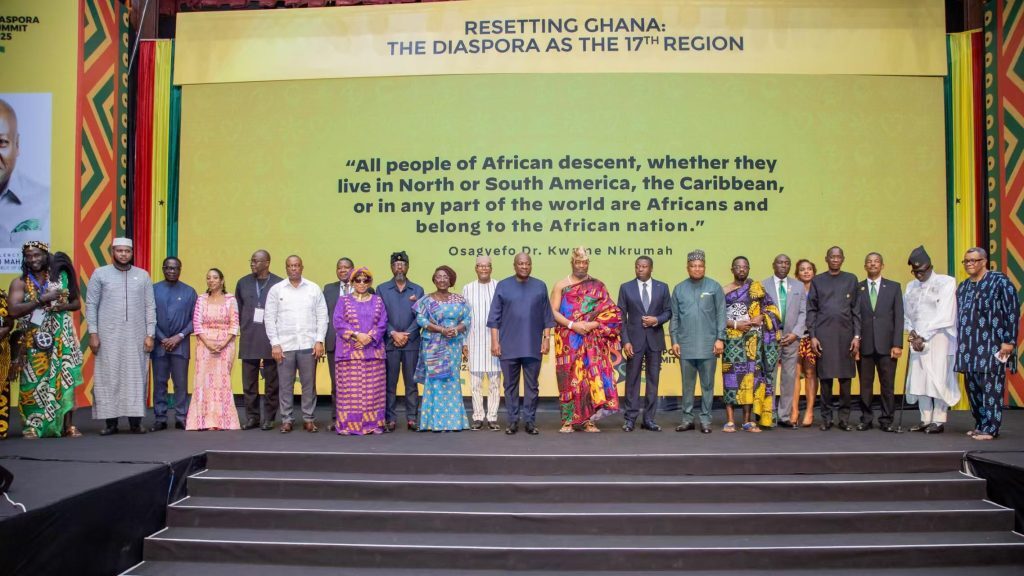

At the eagerly anticipated Diaspora Summit 2025, held December 19–20 at the Accra International Conference Centre (AICC), a powerful and unflinching message echoed through the halls: Africa and its global diaspora remain bound by the unfinished business of colonisation.

Held under the auspices of H.E. John Dramani Mahama, President of the Republic of Ghana, through the Diaspora Affairs Office at the Office of the President and in collaboration with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the summit convened African and diaspora leadership from across the world. Among those present were H.E. Faure Gnassingbé, President of the Council of Ministers of the Togolese Republic, senior government officials, development partners, private-sector leaders, and Ghanaians and Africans from across the diaspora.

Key issuance

The Summit culminated in the issuance of key recommendations to advance African-diaspora collaboration and reparatory justice. These keys include:

1. Establishing transparent mechanisms to manage reparations

2. Ensuring reparations go beyond money, including debt cancellation, return of artefacts, institutional reform, and economic empowerment

3. Mobilizing Africa’s intellectual capital and civil society

4. Creating structured dialogue between governments and the diaspora

5. Accelerating diaspora investment and foreign direct investment, and

6. Promoting unity and coordinated global action among African states and people of African descent

But it was President Mahama’s address that defined the summit’s historical weight.

A continent and a people divided

Speaking candidly, President Mahama traced the deep fractures that continue to weaken African and Black progress globally. He pointed to coups, conflicts, and externally imposed political instability as tools that have kept Africa fragmented, while so-called anti-poverty programmes have often failed to address the structural roots of poverty itself.

“These systems,” Mahama argued, “were never designed to empower us — only to manage our suffering.”

The war of images against Black people

One of the most striking moments of the address was Mahama’s warning about a systemic war of images waged against Africans and Black people worldwide.

He described how Africans are routinely portrayed as primitive, violent, and intellectually inferior, incapable of self-determination, while Black people in the Americas are stereotyped as lazy, drug-addled, and criminally inclined. These narratives, he emphasized, are not accidental — they are manufactured to foster fear, justify exploitation, and instill self-hatred.

This selective broadcasting of images, Mahama warned, does long-term psychological damage, shaping how the world sees Black people — and how Black people come to see themselves.

Colorism: colonialism’s living legacy

President Mahama also confronted colorism, describing it as one of colonisation’s most enduring and insidious effects. The idea that everything Black is negative or inferior, and that proximity to whiteness is more desirable, has seeped into beauty standards, leadership perceptions, media representation, and social hierarchy.

Even language, he noted, reinforces this conditioning — where “black” is synonymous with evil, danger, or corruption, while “white” suggests purity and virtue.

“Colonisation,” Mahama stated, “did not leave us unscathed.”

Psychological chains after political independence

While African nations may have achieved political independence, Mahama argued that mental and cultural independence remains incomplete. Colonial systems reshaped education, governance, religion, and economic structures to center European norms and values, leaving generations conditioned to doubt their own identity, history, and capacity for leadership.

This psychological inheritance, passed down across generations and oceans, explains why overcoming colonisation remains such a profound struggle for Africans on the continent and Black people across the diaspora.

Flipping the script

Yet Mahama’s message was not one of despair — it was a call to action.

He urged Black people globally to take the entire colonial modus operandi and flip it — then reverse it. The same forces once used to demean Blackness, he argued, must now be transformed into tools of empowerment, pride, and unity.

This reversal requires:

- Reclaiming Black identity as strength, intelligence, and creativity

- Controlling our own narratives, media, and imagery

- Building economic systems that serve African and diaspora communities

- Strengthening political and economic ties between Africa and its global diaspora

- Intentionally unlearning colonial conditioning

Why the struggle endures

The reason the struggle against colonisation remains so difficult, Mahama implied, is because colonisation succeeded not only through force, but through internalisation. It trained the colonised to police themselves — through shame, division, and aspiration toward whiteness.

Undoing that damage is neither automatic nor easy. It requires conscious resistance, unity across borders, and the courage to imagine systems beyond those inherited from colonial rule.

A defining moment

The Diaspora Summit 2025 marked more than a conference — it was a reckoning. By naming the psychological, cultural, and structural dimensions of colonisation, President Mahama challenged Africa and its diaspora to confront uncomfortable truths and reclaim agency over their future.

The message from Accra was clear: freedom is not only about sovereignty — it is about self-definition. And until Black people everywhere control their own image, systems, and destiny, the work of decolonisation remains unfinished.